The Local Approach

Kevin Dooley, Jacob Bethem, William Campbell and Carole Mars

This is the first in a series of articles called “Steps to Circularity” that will explore a variety of different projects and viewpoints connecting the business of recycling to the wider circular economy movement.

Municipalities face challenges when trying to provide value through their waste management services. There is increasing pressure on communities to divert as much waste from landfill as possible, and local officials are also tasked with measuring and communicating their waste diversion performance to citizens and city government.

Today, in addition to fulfilling their traditional sanitation mission, municipal public works organizations are also expected to do business development, as residents and the local government expect them to create revenue and jobs for the city.

With these factors in mind, the city of Phoenix recently recently established the “Reimagine Phoenix: Transforming Trash into Resources” initiative in support of its goal to divert 40 percent of its waste away from landfill by 2020.

In order to explore different ways of measuring and communicating waste diversion and recycling success to the City Council and residents, the Phoenix Public Works Department partnered with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Service and The Sustainability Consortium at Arizona State University to perform research on diversion metrics.

As part of that effort, the research team created a conceptual framework to help identify the steps that a city could take to improve waste diversion and recycling – or more generally, to become more of a circular economy in which we move away from the current linear model of make-use-dispose.

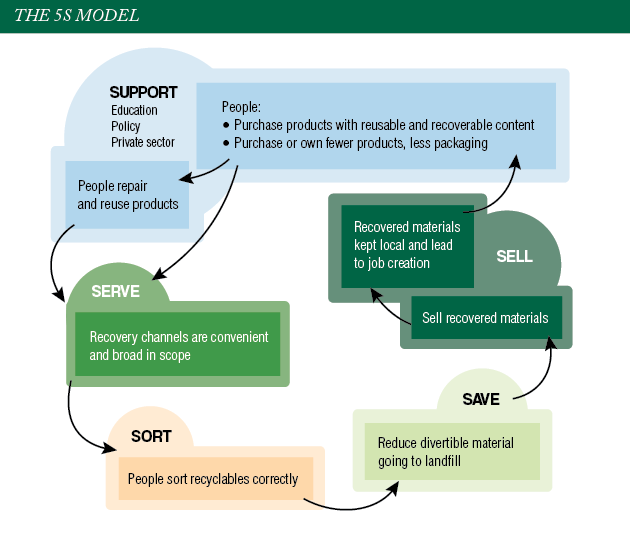

This article describes our “5S Model” for circularity in a city, which boils down to five tenets: support, serve, sort, save and sell.

It is a simple framework that communicates what a city can do to create a more circular economy. It can also be used to help a city plan its strategic waste management goals and actions; to identify strengths, weaknesses opportunities, and threats in existing programs; and to serve as a template for measuring circularity success.

Taking cues from world of public health

In seeking ways to think about success in circularity, our research team was inspired by the United Nations’ UNAIDS 90-90-90 program.

AIDS is a complex and nuanced issue in which planning, measurement and communication are key factors. Traditionally, health care leaders articulate goals and progress with difficult-to-understand metrics, like mortality rates. UNAIDS identified a pathway to success for managing and treating AIDS. A person has to: (1) know they have HIV/AIDS, (2) get treated, and (3) get better. If all three happen, a successful outcome is achieved.

This campaign led to the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal – 90% of people living with HIV will know their status; 90% of those infected with HIV will get treatment; and 90% of those treated will have viral suppression. It gave planners and leaders a simple way to think about and communicate what was needed for success.

We asked the same question: What are the steps that, if taken, will lead a city to be more successful in creating a circular flow of materials? Our 5S Model, shown in the figure below, is formulated around those steps.

A model for circular success

Not to be confused with “5S” from lean manufacturing, our 5S Model suggests that circularity can be achieved by way of a clear path that takes into account a handful of important realities.

City residents have their own role in making a city more circular. First, they can purchase products with reusable or recoverable content. Second, they can purchase or own fewer products or purchase products with less packaging, which reduces waste. Finally, they can repair, refurbish and reuse the products they own.

Meanwhile, the city and its commercial partners need to provide convenient recovery channels for the recyclable material to be collected, and residents need to correctly sort their waste from recyclables. The city can also engage in additional activities that recover materials bound for landfill after being disposed by residents.

Finally, recovered material can be sold for revenue. If recyclers or remanufacturers are local, then it can also lead to local job creation.

The 5S Model takes those basic facts of material use and recovery and outlines five distinct areas where a municipality can take clear action.

Support: What can the city do through education, policy or public-private partnership that can help residents purchase reusable, repairable and recyclable products and packaging?

Serve: To what extent has a city provided convenient and easy-to-use channels for recovering recyclable materials?

Sort: How well do residents successfully separate trash from recyclables?

Save: What additional steps does a city take to minimize waste to landfill?

Sell: What economic benefit does the city and its commercial partners gain from recovery and recycling of materials?

Implementing and measuring 5S

In this section, we will share some examples of how cities (and, in some cases, state governments) have implemented various elements of the 5S Model and how performance can or cannot be easily measured.

When it comes to “support,” the politics and culture of a jurisdiction will shape to what extent it can drive regional change. Some cities are more aggressive in use of regulatory power or collaboration with the private sector.

For example, the city of Austin, Texas promotes repair through its Fix-It Clinics, where residents can find a repairer or learn to make their own repairs. Some cities and states have used financial (dis)incentives to reduce use of unwanted materials or to encourage their collection. For instance, San Francisco’s plastic bag ban, enacted in 2007, is now effective statewide. In 2020, California has also made it illegal to offer plastic straws by default. Restaurants may only provide plastic straws upon request or face a $25 fine.

The measurement of the “support” dimension is more likely qualitative than quantitative. From 2001 to 2008, however, California surveyed its residents and organizations to measure landfill diversion. Activity such as use of e-billing or composting yard waste was counted toward an overall landfill diversion rate.

Moving to “serve,” cities can make it easier or harder for residents to get recyclables successfully into a formal recycling stream. For example, San Francisco offers residents a free compost pail, free home hazardous waste pick-up, and a free program geared toward collection of medical waste and syringes. Medford, Mass., meanwhile, utilizes a pink bag for curbside clothing collection. And Boulder, Colo. created a Center for Hard-to-Recycle Materials (CHaRM) for electronics, a variety of plastics and miscellaneous materials such as concrete.

In order to measure the “serve” dimension, a city has to take into account the convenience of their programs. Is curbside pick-up the only channel to be considered convenient, or does a bin at a local shopping mall count? How far do residents have to travel to get to a specialty recovery facility for materials such as electronics or organics? Measurement of “serve” also requires the city define what materials are considered recyclable and whether it matters if the channel is being offered through a private entity, such as a service that picks up used carpet or building materials.

A number of possible actions fall into the “sort” section. Research shows that educating residents as to what can and cannot be recycled is a key driver of improving the sorting that residents do. In Phoenix, an auditing process is used to see how much contamination is in a household’s recycling bin, and the resident either gets an “Oops” or “Shine On” sticker for the outcome.

Success in the “sort” dimension is typically measured by two rates – percent of recyclables that contain non-recyclables, and percent of non-recyclables that contain recyclables. Most cities or commercial partners pay more attention to the first metric, as this impacts the quality of recovered material, the cost to remove contamination, and the market price obtained for the recovered material. As with “serve,” measuring “sort” requires a city to define what materials are considered recyclable in order to calculate rates. Planners also must determine whether to include bulk recyclables (carpet and e-scrap, for instance) or organics as part of the accounting.

This brings us to what cities can do to “save” additional tonnages from going to disposal. In Phoenix, the city has implemented a common-sense practice: If operators within the transfer station see a large heap of yard waste, they can extract it and send it instead to the organics composting stream.

Technological advancements could create more opportunities for more “save” actions. Last year, for instance, a sortation pilot project was established in Portland, Ore. to study the possibility of recovering mixed plastics from loads of residue at regional MRFs. The practice of landfill mining is also a strategy that has been discussed in different areas across the globe.

Technological advancements could create more opportunities for more “save” actions. Last year, for instance, a sortation pilot project was established in Portland, Ore. to study the possibility of recovering mixed plastics from loads of residue at regional MRFs. The practice of landfill mining is also a strategy that has been discussed in different areas across the globe.

Finally, there is the need to “sell” the benefits of materials recovery to the wider community. The recent collapse of the recycling markets has decreased revenue for cities and commercial partners, making it harder for cities to justify continued operation of recycling. For that reason, it is important for cities to consider ways to change the dialogue from measuring revenue from commodity materials sales to measuring benefits like the number of jobs created through local remanufacturing. For example, in a recent report the National Resources Defense Council estimates that achieving a 75 percent recycling rate in California has the potential to create at least 110,000 additional recycling jobs.

The path to progress

A city can become more circular in its materials by (1) supporting the local circular economy through education, policy and public-private partnerships, (2) serving residents with convenient channels for material recovery, (3) educating residents how to sort materials correctly, (4) taking action to maximize recovery of recyclables or compostables, and (5) selling the recovered material for revenue, ideally locally so local jobs are created.

Kevin Dooley is chief scientist of The Sustainability Consortium and Distinguished Professor of Supply Chain Management in the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. Jacob Bethem is a visiting assistant professor of sustainable business at the University of Redlands. William Campbell is a project manager at the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainable Solutions Service at Arizona State University. Carole Mars is director of technical development and innovation at The Sustainability Consortium.

Contact the authors at kevin.dooley@asu.edu.